Mark Feldman, Interim Dean and Professor of Law of Peking University School of Transnational Law("STL"). He previously served as a member of the T20 Saudi Arabia Task Force on Trade, Investment and Growth, as a member of the E15 Initiative Task Force on Investment Policy (World Economic Forum/ICTSD), and as Chief of NAFTA/CAFTA-DR Arbitration in the Office of the Legal Adviser at the U.S. Department of State. As Chief, he led the team that represents the United States in investment treaty arbitration and provided legal counsel supporting the negotiation of U.S. bilateral investment treaties and investment chapters of free trade agreements (including TPP and U.S.-China BIT negotiations).

Professor Feldman’s government experience also includes service as a law clerk to Judge Eric L. Clay on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit and as a Peace Corps volunteer in Lesotho during South Africa’s transition to democracy. In the private sector, he practiced law for several years at Covington & Burling. Professor Feldman holds a BA from the University of Wisconsin, where he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa, and a JD from Columbia Law School, where he was a James Kent scholar, Harlan Fiske Stone scholar, and recipient of the Parker School Certificate in International and Comparative Law.

Q1: You hold a BA from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where you were elected to Phi Beta Kappa. Could you share some stories from your college days with us?

Wisconsin is a great public university with exceptional faculty and one of the most progressive campuses in the US. Madison is one of the best university towns in the US. Wisconsin is a hub for brilliant, motivated people, many of whom are working at the highest levels in their fields.

When I first arrived at Wisconsin, I was only 17 years old. Wisconsin is a large public university with a wide array of course offerings. It was overwhelming for me when I arrived because I was unsure of the direction I wanted to take. One of the courses I took in my first semester was an introduction to philosophy, taught by Professor Elliott Sober. I had this moment, feeling a real connection to philosophy, realizing that I had a talent for it. I went on to take many philosophy courses, including some in legal philosophy. I started accumulating political science credits as well. Soon, I realized that I would have enough credits for a double major. I decided to pursue the double major in philosophy and political science, although I have always had a deeper connection to the philosophy major. I also took an undergraduate constitutional law course with Professor Joel Grossman, which I loved. That course definitely encouraged me to start thinking more seriously about law as a possible career path.

Q2: After graduating from college, you served as a Peace Corps volunteer in Lesotho. What made you decide to volunteer for the Peace Corps? Could you share some stories from your time as a volunteer? You were in Lesotho from 1992-1994, during South Africa’s transition to democracy, a time of considerable turmoil in South Africa. Can you share your observations from that time?

I worked very hard at Wisconsin, immersing myself in my studies, which I thoroughly enjoyed. But I felt a need for a break from academic life and was interested in a unique experience in the developing world. At the time, I was uncertain about whether to go to law school or continue in philosophy. I wanted to take some time to think it through.

Serving as a Peace Corps volunteer has been something of a Wisconsin tradition; Wisconsin is consistently among the top universities in the US in terms of the number of graduates who go on to serve as Peace Corps volunteers.

Peace Corps applicants can specify a region, and I selected Africa, which was probably the region that was most closely associated with Peace Corps. The response I received from Peace Corps was that there were two available locations in the region: one in Namibia and one in Lesotho. It was a difficult decision to make. Peace Corps’ Lesotho program was the more established of the two; even in the '90s, Peace Corps had been in Lesotho for more than 20 years, while the Namibia program was just getting started. I finally decided to go to Lesotho.

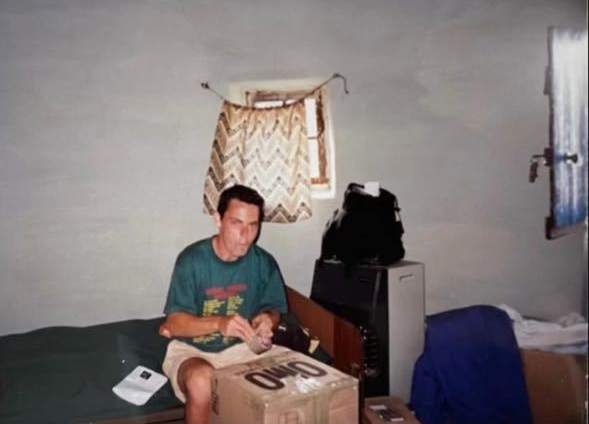

In November 1992 I arrived in Lesotho, a country surrounded by South Africa.I was 21 years old. I was going to be teaching at a secondary school. I remember the school headmaster taking one look at me when we met and saying, “he's young,” probably because I looked about 17. In Lesotho, I taught English and Science and also worked on HIV/AIDS education. My students were secondary school students, generally around the age of 15. Some were older because they had taken some time off. I was not much older than some of the students. I received positive feedback from the students; I found the classroom to be a good environment for me. I would remember these experiences when considering a move to law teaching much later in my career.

Lesotho is a sovereign country, but because of its geographic location, the culture, politics and economy of South Africa were inescapable. I actually lived very close to the border with South Africa; most of the view from the village where I stayed was of South Africa. It was an incredible moment to be there: when our Peace Corps group arrived in 1992, Mandela had been released from prison only a few years before. In 1992 and 1993, it was widely anticipated that Mandela would be elected President, but it was not at all certain that South Africa’s transition to democracy would be smooth. People were bracing for real conflict. Looking back at the successful transition in April 1994, it is just extraordinary. In terms of inspirational figures in my lifetime, for me, no one will come close to Nelson Mandela. After spending nearly three decades in prison, he reemerged ready to lead the country, seeking unity rather than vengeance. The country truly rallied behind Mandela in 1994. There was incredible goodwill at that moment, with the country standing firmly behind Mandela as their leader.

There are still things that take me back to South Africa in the '90s. One is Cyril Ramaphosa, who is the current president. When I was in South Africa 30 years ago, Ramaphosa's name was everywhere. At the time, he was the secretary-general of Mandela's African National Congress party. Another powerful reminder is the South African flag. South Africa’s transition to democracy in 1994 was accompanied by the introduction of a new flag, one that was completely transformational. The flag's “Y” shape can be interpreted as symbolizing the unity and coming together of the country. What was truly powerful at the time was seeing this new flag flying everywhere on the streets of Johannesburg in 1994. Witnessing South Africa in 1994 was incredibly moving. I knew then that I probably would not experience such a transformational moment again in my lifetime.

Q3: What do you believe was the most significant impact of your experience as a Peace Corps volunteer in Lesotho? Could you elaborate on that for us?

I learned so much during my time in Lesotho. Perhaps the most important insight was that if you genuinely want to understand a place, you have to spend time there, on the ground. When I first arrived in Lesotho, I had a conversation with an official from the US Embassy. The situation at that moment, in late 1992, was quite volatile. The official said, as I remember the conversation, “If you want to understand what’s happening here, don't focus on race.” I found this surprising because the coverage of South Africa in the US at that time seemed to focus only on race. His insight was invaluable, as there were important issues unrelated to race, such as federalism and the distribution of power in the new system, that were driving events. Alliances transcending racial lines were forming in support of a more decentralized system. This was an understanding that I gained only by living in that particular place at that particular time.

Entertainment provided another perspective on the importance of living in a place in order to be able to even begin to understand it. When I was preparing to move to Lesotho, in terms of South African music, I was only familiar with Ladysmith Black Mambazo and Miriam Makeba. Ladysmith Black Mambazo was known to everyone in the US for their collaboration with the well-known Paul Simon. Miriam Makeba, a major pop star, also had achieved considerable fame in the US. But when I arrived in South Africa, I quickly learned that Brenda Fassie, at that moment, was the dominant voice in pop music. Her music was everywhere: in the supermarket, in the village, at the bus rink. It's another illustration of how you need to be in a place to begin to understand what is happening there.

I noticed another example of this important insight earlier this year, in reporting from the Shangri-La Dialogue, which is an annual intergovernmental security summit held in Singapore. Based on reporting that I saw, a senior US official was asked about the centrality principle of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), under which ASEAN, as a regional organization, views itself as playing a central role in any regional initiative in the Asia-Pacific region. The US official was asked how US strategy in the Indo-Pacific might interact with ASEAN’s centrality principle.From the reporting that I saw, it appeared, at least in that moment, that the US could have been more focused on that issue. But if you are based in the Asia-Pacific region, where ASEAN’s centrality principle is a major, daily focus of attention, the significance of the principle for any US strategy in the region would be clear. Again, being based in the region contributes to that understanding.

Q4: You recently mentioned that one reason you volunteered for the Peace Corps was because you were considering whether to study philosophy or law. You later pursued a J.D. at Columbia Law School. Could you share the reasons behind your decision to attend law school? Could you share what your life was like at Columbia Law School?

My Peace Corps experience definitely contributed to my interest in law school. One aspect of that experience does stand out. As I was nearing the end of my Peace Corps service, I met with a Peace Corps official to discuss my transition back to the US; the official asked me about my future plans. I said that I was considering either graduate work in philosophy or law school, and that I had not yet decided. Without hesitating, the official said I should go to law school. I asked him why. He said, “because I have a Ph.D. in philosophy.” I decided to go to law school.

I could share a bit about my time at Columbia Law School. Last year, the legendary legal theorist Professor Joseph Raz passed away. He had been my professor at Columbia. His passing made me realize, in a way that I hadn't before, how many legends I had been able to learn from at Columbia, how fortunate I had been to be at Columbia at that moment in time.

One was Professor Oscar Schachter, who had been actively involved with the United Nations in the 20th century and had taught at Columbia since the 1970s. Another, Professor Louis Henkin, had been a pioneer of human rights law and a giant in the field of international law generally. Another, Professor Jack Greenberg, had worked alongside Thurgood Marshall in the famous Brown v. Board of Education case before the US Supreme Court; Marshall later would go on to serve as a renowned Justice on the Court.

The course I took with Professor Greenberg, on South Africa’s Constitution, was co-taught by Justice Albie Sachs. Justice Sachs, who was then serving on the Constitutional Court of South Africa, was a key architect of South Africa’s Constitution. I also was able to take a class with Professor E. Allan Farnsworth, whom you probably know from our Contracts class, since he led the development of the Restatement (Second) on Contracts. I remember being in another class and spotting Professor Farnsworth walking down Broadway. Another student in the class also saw him and said, “Oh my, it’s E. Allan Farnsworth!” All of these professors were legends.

Another one of my professors, Professor George Bermann, is still active today. I occasionally still see Professor Bermann; I struggle to call him by his first name and prefer to address him as Professor Bermann. I also took a course with Professor John Manning, who later went on to teach at Harvard Law School and has served as the dean there for several years.

Again, I feel so fortunate to have been at Columbia at that particular moment in time, when all of those legends were walking the halls. I was able to learn from each of them - such different teaching styles, perspectives and interests. But each of them committed to excellence.

Q5:Could you share your most memorable experiences or stories at law school?

One quite memorable moment for me would be my first class in Contracts, which also happened to be my first law school class ever. The course was taught by Professor Barbara Black. In my section, which was a large one with over a hundred students, I was the first student to be called on. Professor Black used a microphone, and I remember so clearly her looking down the list of student names before finally calling: “Mark.” “Feldman.” I just thought, “This is not happening.” I remember Professor Black asking, in a low, serious tone, a UCC question about the meaning of “cover”: “What do they mean by ‘cover’?” I survived.

There’s a related story about Professor Black. The library was on the third floor, and many faculty offices and lounges were on the upper floors. A group of us were on the first floor and got onto the elevator, including Professor Black. Everyone was going to the upper floors; no one was stopping on the third floor. But the elevator usually would stop on the third floor, because that’s where the library was. In the crowded elevator, someone who was clearly in a hurry said, “I just know we’re going to stop on three.” Professor Black, standing in the back of the elevator, responded: “You're a pessimist.” Just perfect.

Q6: Life at law school is indeed unforgettable. Looking back, what do you believe was the most significant impact of your J.D. program at Columbia Law School on you? Alternatively, what was the most valuable lesson you learned there?

The most important thing that I take away from Columbia is being able to hold my own among incredibly talented people. The level of talent is intimidating, of course. But over time, I learned that I truly did belong there, that I could compete, at any level and in any situation. Making peace with, and maintaining your confidence in, a challenging, competitive environment is crucial. Learning to thrive in a stressful environment is necessary, as you have to realize that competition and pressure are what await you in the professional world. A J.D. program at the top level provides the kind of transition that students need to be able to go on and compete and thrive at the highest levels.

Q7: We often refer to “J.D. education” as a “professional education.”How do you interpret “professional” or “professional education”?

For professional legal education, you are preparing to practice as a lawyer, a profession that includes, and requires, particular standards, particular responsibilities, and particular conduct. You are part of a larger community. Professional legal education prepares students for the transition to becoming a member of this profession, where you will be held to a higher standard in terms of intellectual rigor and integrity.

Q8: Did you contemplate your future career path in law school? For instance, did you ever consider moving toward arbitration at law school? How did you gradually determine your career path? Could you share some stories and insights from your legal practice?

While I was in law school, Professor Bermann was very much on my radar, and I was considering international arbitration. However, in the short term, I was mainly trying to learn the landscape of the different law firms and practice areas. I had a general interest in international practice, but it was not fully developed at that point. I spent a year at Shearman & Sterling doing international transactional work. However, I soon realized that my real talents were in writing, developing arguments, presenting arguments. In transactional work, I wasn’t making good use of those talents. That’s when I began considering a transition to working on disputes in general, whether litigation or arbitration.

As a part of that transition, I served as a law clerk for Judge Eric L. Clay on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. This was particularly rewarding as it was in Detroit, my hometown, which allowed me to be close to family. It was memorable and valuable to experience life in chambers and to be able to watch different advocates arguing their appeals. I was able to see a broad range of styles. On the 6th Circuit, oral arguments are heard in Cincinnati; I made many trips to Cincinnati for the arguments. I was so fortunate to be able to learn from the Judge, my co-clerks, as well as the top lawyers who argued many of the appeals. The entire experience reinforced for me what it means to perform at the highest level.

After completing my clerkship, I transitioned to Covington & Burling in Washington, DC in 2001, focusing on litigation and arbitration, including some work on bilateral investment treaties (BITs). Although I didn't work directly on investment treaty cases at Covington, I did work closely with Stuart Eizenstat on issues relating to investment treaties.

During my years at Covington, two lawyers I had the opportunity to work with stood out. The first, as I mentioned, is Stuart Eizenstat. The second is Lanny Breuer. Both had previously served at senior levels in government. Stu Eizenstat had served as the US Ambassador to the European Union and as the Deputy Secretary of the US Treasury. Lanny Breuer had served as Special Counsel to President Bill Clinton.

Having the opportunity, as a junior associate, to work with such distinguished lawyers was extraordinary. The training is incredible. When working with people who have served as such senior levels, you must be able to distill very complicated situations down to their essence. These are individuals who do not have much time, and normally you only have a minute or two to communicate the complexity of a situation, its essence, the core choices that must be made. Again, incredible training. Looking back, it is striking that both Stu and Lanny treated me, as a junior associate, as well as anyone has treated me throughout my career. Part of that is due to who they are as individuals, but part might also be due to just how senior they were: when someone works at such a senior level, my sense is that you tend to be focused on good ideas and arriving at the right answers, and you tend not to be as focused on internal hierarchies. If a good idea comes from a junior associate, it’s a good idea. If the right answer comes from a junior associate, it’s the right answer.

Q9: You served as attorney-adviser and Chief of NAFTA/CAFTA-DR Arbitration in the Office of the Legal Adviser at the U.S. Department of State. Could you share some stories from your work in the Office of the Legal Adviser at the U.S. Department of State?

Similar to how many Wisconsin graduates go on to serve as Peace Corps volunteers, I think it is fair to say that many Covington lawyers go on to serve in the U.S. Government, including the U.S. State Department.

I worked in the Office of the Legal Adviser at the U.S. State Department. There were a few hundred lawyers there at the time. Much like my clerkship, this proved to be such a valuable experience for understanding the internal dynamics of incredibly important institutions. Throughout my time at the State Department, I worked primarily on investment treaty issues, focusing mostly on disputes and occasionally on negotiations. I was able to spend five and a half years working almost exclusively on investment treaty issues. That kind of experience is, of course, quite rare; government experience is simply unique.

For the first half of my time at State, John Bellinger served as Legal Adviser. For the second half, Harold Koh served as Legal Adviser. The Legal Adviser works closely with the US Secretary of State; it is difficult to overstate the importance of the position.

I was able to work with Harold Koh on one investment arbitration case, Grand River Enterprises v. United States. In US practice, the Legal Adviser at times has participated in investment arbitration cases. But Harold ultimately spent a significant amount of time with our legal team on the case, which was extraordinary, given that Harold was working on so many other matters, across many different areas of international law. Harold made a detailed opening argument in the case, which actually is still available on the State Department website. It was inspiring to see someone in such a senior position investing a very significant amount of time on the case.

There is actually a connection between the Grand River case and the conference I co-chaired with Dr. Crina Baltag earlier this year, in Washington D.C., the ITA-ASIL Conference (Institute for Transnational Arbitration/American Society of International Law). Our keynote speaker was Professor Hélène Ruiz Fabri, who is based at the Sorbonne Law School. Professor Ruiz Fabri spoke on the groundbreaking topic of intersectionality and international arbitration. Originating from critical race theory, intersectionality recognizes that different social identities - such as race, gender, and sexual orientation - can overlap and interact to create new forms of discrimination and disadvantage that existing law might not be fully equipped to address. In her keynote address, Professor Ruiz Fabri framed intersectionality as a “theory of complexity” and discussed complexities associated with three recent investor-state disputes. Professor Ruiz Fabri emphasized that such complexities cannot be adequately addressed through simple, binary approaches to dispute resolution, which tend to focus exclusively on the interests of investors and states. For me, Professor Ruiz Fabri’s keynote address brought to mind many cases, including the Grand River case, given that some of the arguments raised by the claimants - who were members of Canadian First Nations - concerned rights of indigenous peoples under international law.

Q10: You joined STL in 2011. At that time, STL was only three years old and was still a nascent institution with a relatively small number of students and professors. How did you come to know about STL? What factors influenced your decision to join STL?

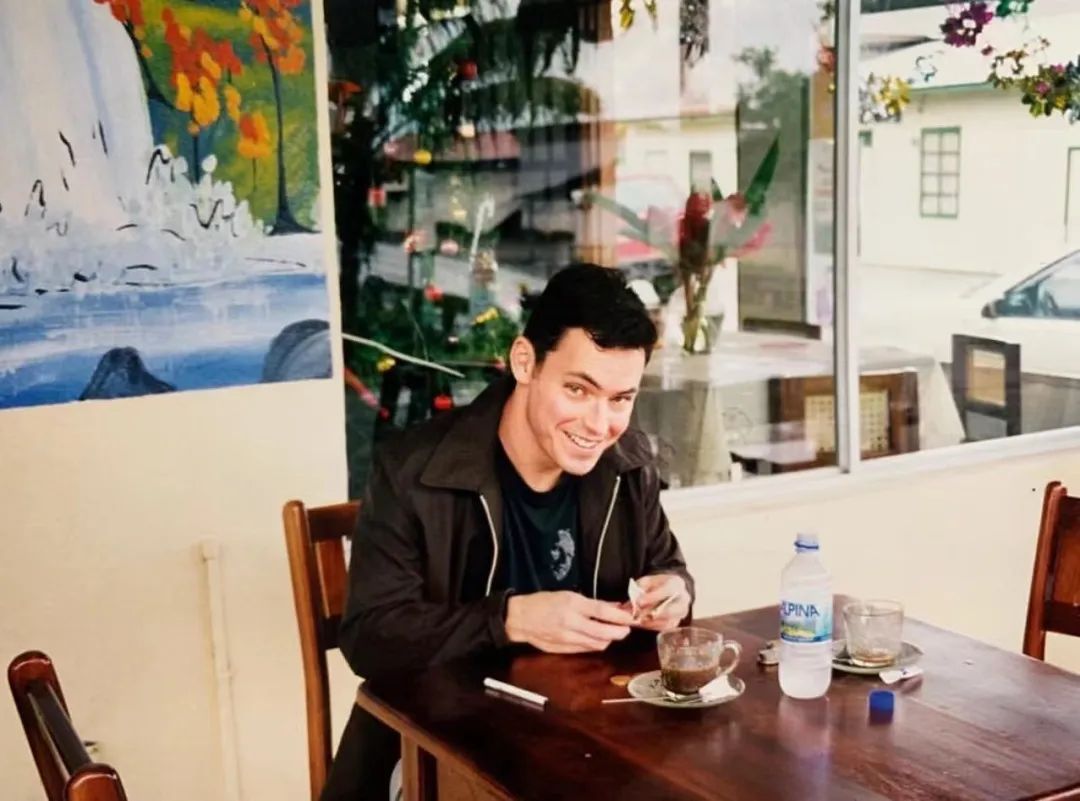

I first learned about STL during my commute to the US State Department. I would take a short bus ride to the metro, and I remember one day in 2010, just as I was about to get on the bus, I was checking my email. I saw that I had received an email from Dean Stephen Yandle. I read the email, which contained a lengthy description of STL. STL sounded quite interesting; clearly a new, ambitious venture. Later, I met with Founding Dean Jeffrey Lehman and Dean Yandle in Washington, D.C., which eventually led to a visit to the STL campus in February 2011.

Working at the US State Department also provided a nice transition to STL because I had been supporting some of the early rounds of the U.S.-China BIT negotiations. That was my first experience with China as a rule-maker. It was clear, around 2010, that China’s level of international engagement was increasing rapidly.

Harold Koh actually played a significant role in my transition to STL. In 2010, when I was considering a move to teaching and talking to several schools in the US, I approached Harold. Having been on the Yale Law School faculty for many years, Harold was, of course, an excellent source for advice. Harold saw that STL was on the list of schools that I was talking to. Harold knows Founding Dean Lehman and Dean Yandle quite well, and his advice was that I should go to STL. At that time - in 2010 - STL was still quite new, with a small number of faculty and students. When I ultimately decided to join STL in early 2011, the decision required, to some extent, a leap of faith. The strong support from Harold Koh played a significant role in my decision. My experience on the STL campus in early 2011 - including a significant amount of time spent with Founding Dean Lehman and Dean Yandle - also was a major factor, of course. The decision also required incredible support from my family. Nyaguthii Chege and I were raising two young kids at the time. Nyaguthii supported the move and actually worked at STL for two years, from 2012 to 2014. Our kids were incredibly open-minded and adaptive. Without such family support the move would not have been possible.

Q11: We noticed that your career path involved several transitions, unlike some legal practitioners whose careers follow a linear trajectory. Did you feel pressure or uncertainty each time you made a career transition?

There certainly has been stress and anxiety, but I’m probably a bit more comfortable with risk than some lawyers, who are often quite cautious, for good reason. I greatly value interesting experiences. When I was 21, I moved to Lesotho and experienced South Africa’s transition to democracy. Having had such an experience early in life, I realize that I probably will never be able to recapture quite that level of excitement and electricity, but I do constantly look for interesting experiences, experiences where I am trying to absorb and comprehend as much as I possibly can. My priorities have led to a career that has not been conventional.

Q12: Could you describe what STL was like in its early days? What was the atmosphere like? How do you think STL has changed over the years?

STL’s environment in the early days was quite different. STL was relatively small, with a 1L class of around 50 students. The faculty was also small, and we all knew each other well. The U.S.-China relationship in 2011 also was quite different from what it is today. At that time, most of the faculty were American, and we had world-class professors from top U.S. schools joining us. It was exhilarating to have academic giants like Matthew Stephenson and Jack Goldsmith walking around campus. Everything felt new, full of possibility.

STL recently celebrated its 15th Anniversary. Over the past 15 years, we have undoubtedly become a more mature and established institution. Like any institution, maintaining the initial level of excitement is extraordinarily difficult. We also have been experiencing two important shifts, one generational and one economic. The current economic situation in China is more challenging than it has been in the past - particularly for recent graduates - and we also have a new generation of students that, due to a variety of factors, are facing issues of anxiety and depression at levels that earlier generations did not experience.

But on our 15th Anniversary, we also must keep in mind the many advantages that STL now enjoys, precisely because STL is now an established institution. In the early years, STL students often had to explain what STL was to potential employers. Now, that's no longer necessary. People know who we are. Many of our graduates now hold senior positions in a range of leading institutions, not only global and Chinese law firms but also international organizations, multinational enterprises, SOEs and government. As we transition to a more mature phase, with STL graduates occupying leadership positions throughout China and to some extent abroad as well, we need to constantly be strengthening ties with this outstanding global network of professionals. This is an invaluable network that simply was not available to STL students in the early years.

I also would emphasize that the size of our alumni network is increasing at a faster pace than in prior years, due to the very significant growth in our class size under the leadership of Dean McConnaughay. When Dean McConnaughay joined STL in 2013, the size of our 1L class was a fraction of our current 1L class, which now is about 150 students.

Q13: You mentioned increased anxiety levels at STL and noted that young people from different generations face unique pressures and challenges. Could you expand on your observations regarding the different pressures each generation faces? How do you think we should cope with these pressures?

In the early days, STL students were what I’d call millennials, and you’d probably think of as the 1990s generation. Today’s students are what I’d call Gen Z, but you might refer to them as the 2000s generation. Comparing the two, it is clear there is a significant generation gap. For purposes of that gap, I think the key turning point was around 2010, when the social media platforms gained momentum. For that reason, there is a real generational difference between someone born in, say, 1992, and someone born in 1998: for the person born in 1998, the “post-2010” world of YouTube, Instagram, Twitter, Weibo and WeChat is basically the only world they have ever known. I discussed this generation gap at STL’s 10th Anniversary, in a talk I called “Generation STL.”

STL students reflect this generation gap. Anxiety and depression issues, due in significant part to social media, have become more pronounced in recent years. I have had personal experience with these issues in my own family. For Gen Z, social media has played a major role in their entire life experience, which contributes to many anxiety-inducing factors, including the fear of missing out, constant self-comparison, and presenting an idealized, unrealistic version of oneself. Gen Z also has had to face a pandemic, an increasingly demanding and competitive job market, climate and sustainability concerns, and intensifying geopolitical challenges, which further contribute to heightened anxiety levels. It is essential to address these concerns and consider ways to alleviate anxiety in any educational setting. Particularly with respect to STL, our unique, multicultural law school environment requires us to be aware of our cultural differences and particularly mindful of our conduct. Behavior that might be acceptable in one culture might not be acceptable in another. As faculty, students and staff, we must make a special effort to work together on reducing stress and anxiety. A certain amount of stress and anxiety at law school is, to some extent, unavoidable, but we must make sure that such levels remain reasonable and manageable.

Q14: What motivates you to continue working and teaching at STL after more than a decade?

Part of the reason I have stayed at STL is my love for being in the classroom. There’s never a day when I think, “Oh, I have to teach today.” I don’t have many talents, but I do have a few. I actually had some athletic talent when I was younger, which might sound surprising. I also have a talent for logical reasoning, public speaking, and thinking on my feet. It’s incredibly rewarding to do something you’re good at and that people value. Being in the classroom is simply a great fit for me.

I've been at STL for a long time, and I’m not looking to leave. I have presented at many schools globally and the level of student engagement at STL is matchless. I’ve become accustomed to the energy level here, which is very important to me.

Q15: In your opinion, what kind of talent does STL aim to cultivate, and how have the career paths of graduates changed over time? How does the STL classroom environment foster these talents and prepare students for various career paths?

At Columbia, I remember being surrounded by incredibly talented, ambitious people. Talented, ambitious people tend to go in many different directions, often charting new paths. STL provides a great example of this, as our graduates have pursued so many different, rewarding opportunities, in both the private and public sector. Some of our graduates have become founders of their own companies, which clearly illustrates the value of creativity and imagination. We aim to develop and encourage creativity in the classroom every day. We encourage students to engage deeply, understand different perspectives, and approach issues from various angles. By nurturing creativity, STL prepares students to excel in a wide range of fields and to pursue their passions and ambitions with confidence.

There has been a significant shift in the career trajectories of our graduates since the early days of STL. Initially, the focus had been on placing graduates in large global law firms. However, as the landscape evolved, while some students still join these firms, many others now pursue opportunities in many different areas, including, as I mentioned, prominent Chinese global law firms, government agencies, state-owned enterprises, international organizations and multinational enterprises.

Despite these diverse career paths, the foundational skills learned in the classroom remain consistent. STL students sharpen their analytical rigor, engage with differing viewpoints and perspectives, and develop their capacity for creative, imaginative thinking. STL students also develop core common law skills such as analogizing and distinguishing.

On a higher level, students also learn the importance of engaging with highly talented individuals. They understand the need to be prepared for every classroom session and meeting, recognizing that a lack of preparation will quickly become evident. This commitment to being well-prepared and ready to contribute is an integral part of an STL education, regardless of the particular direction a student ultimately chooses to pursue.

Q16: STL is the only law school in China offering an American Common Law Juris Doctor degree (J.D.) and the only law school in the world that offers both an American law J.D. and a China law Juris Master’s degree (J.M.). We often describe STL as a unique law school. What, in your opinion, makes STL unique?

We are, undeniably, unique. We combine common law and civil law curricula and add a transnational focus. It is worth noting that there has been a surge in the launch of transnational J.M. programs in China in recent years. This underscores the growing recognition in China that transnational skills are essential for legal practice today. But STL remains the only institution in China that combines common law and civil law coursework, taught by resident faculty from around the world. Even with the emergence of transnational J.M. programs throughout China, STL remains, unquestionably, unique.

The composition of STL faculty has evolved over time. Initially, as I mentioned, the faculty consisted mostly of Americans from top U.S. law schools. While STL’s 1L curriculum today still closely follows the U.S. model, with instruction provided mostly by U.S. J.D.s, our upper-level electives offer a more global perspective. This development has been positive for the school, as it maintains a strong American connection while incorporating global perspectives. Our J.M. program also has developed considerably, in significant part through the efforts of Professor Mao Shaowei, who has set an example in the classroom by incorporating a range of highly innovative techniques, including use of the Socratic method and the case method as well as interactive discussions.

Our J.D. program has attracted a lot of attention and, at times, scrutiny. Regarding the value of our J.D., I see connections between the STL J.D. and an honor society in the US called Phi Beta Kappa. (Editor Notes: The Phi Beta Kappa Society is the oldest academic honor society in the United States and the most prestigious, partly due to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal arts and sciences, and to induct the most outstanding students of arts and sciences at only select American colleges and universities.) When I was elected to Phi Beta Kappa at Wisconsin, it was incredibly meaningful to me because I had worked very hard, and it was unexpected. The society’s distinctive emblem is a golden key, the Phi Beta Kappa key, which represents academic commitment and achievement at the highest level. Notably, the key is symbolic: it does not unlock any physical object. Regarding STL’s J.D., it does seem at times that some students, including some prospective students, view the J.D. through what can be seen as an instrumentalist lens, focused on what objects the J.D. might be able to unlock. But in my view, the J.D., like the Phi Beta Kappa key, reflects a certain experience, and a certain level of achievement, that are available only to a small set of distinguished individuals. No other law school in China provides an experience resembling the STL experience. Our J.D. is a signifier of an immensely valuable, undeniably unique experience, as STL students transition to the professional world along a path that has not been replicated anywhere else in China or the world.

Q17: Considering the recent San Francisco summit between the leaders of China and the United States, which achieved a series of accomplishments and added stability to China-US relations while injecting positive energy into world peace and development, what impact do you think China-US relations have on STL?

The recent meetings in San Francisco – and, more broadly, the significant increase in senior level in-person China-US engagement over the past several months – have been quite encouraging. The US-China relationship is, quite clearly, very important for STL. STL was established in 2008, at a moment when the US-China relationship was developing quite well. As I mentioned, around that time, I was working on bilateral investment treaty negotiations between the two countries.

STL’s two founders, Dean Lehman and Hai Wen – who, at the time, was serving as Chancellor of the Peking University Shenzhen Graduate School campus – anticipated that STL could support the development of “bridge people,” that is, people who could deepen connections between China and the rest of the world. As Dean Lehman recently observed at STL’s 15th Anniversary “Birthday” Event, he and Hai Wen specifically anticipated the development of “two important new communities of bridge people”: STL’s Chinese students and STL’s international faculty. Specifically, STL’s students could serve as “bridges from China out to the rest of the world” and STL’s international faculty could serve as “bridges from other countries into China.”

With respect to the China-US relationship in particular, as I observed at STL’s 15th Anniversary event, although the level of engagement between the two countries has fluctuated significantly over the past 15 years, at the working level of our institution engagement has been consistent and strong since 2008.

I also would highlight in particular the significance, for international faculty, of being able to interact with and hear views from a younger Chinese generation. As international faculty at STL, we look forward to hearing student perspectives because we know they often surprise us, in terrific ways. For recruiting international faculty, we need to highlight the value of engaging with our students and gaining insights that they had not anticipated.

Q18: Some students are interested in engaging in transnational practices, like treaty arbitration or international commercial arbitration. But it appears that there are not many such opportunities in China's Mainland. These students might be concerned that fewer individuals will be selected or hired by law firms for transnational legal practice. What are your thoughts on this issue?

Regarding opportunities for STL students, I think there’s a lot of work in the area of international commercial arbitration. I think the next step for China's Mainland arbitration institutions in this area is to manage more cases in English. It also will take time to build confidence, among global users, in China-based arbitration institutions such as CIETAC (China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission) and SCIA (Shenzhen Court of International Arbitration). There are several ways to build such confidence. One is to have top people on your roster and assigning those top individuals, frequently, to cases. Once the global arbitration community sees that top arbitrators are working on cases administered by CIETAC and SCIA, there will be strong reputational gains, but it will take time.

The AIIB (Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank) has been patiently and quietly building a reputation for good governance as a multinational development bank. Earlier this year, there was a very public departure by a Canadian national, which drew a lot of media attention. I'm sure the event was frustrating for the AIIB because they’ve been conducting their business quietly, without any media attention. The high-profile departure, rather than the important, day-to-day work of the institution, is what captured the media’s attention. I believe that institutions like the AIIB, CIETAC, and SCIA need to take a long-term view and continue their daily operations quietly. It’s through quiet, consistent work over time that a reputation is built.

Q19: After many years of legal practice and teaching, what do you find to be the most interesting or attractive aspect of law?

For me, and this is very particular to the world of international arbitration, I really appreciate the ability to bridge the academic world and the world of practice. The opportunity to co-chair the ITA-ASIL Conference was such a great opportunity for me for many reasons; one of the most important is that the annual conference has a reputation for bringing together academics and practitioners. I really enjoy that kind of environment. Conferences that focus exclusively on academic issues, or exclusively on practitioner issues, are less of a priority for me. I prefer environments where the two come together. That’s why in terms of my scholarship, I am always thinking about how to influence policy. Last year, I was invited to share thoughts on China’s draft revised Arbitration Law. That is the kind of opportunity that is most valuable for me, and I provided detailed views in response to the invitation.

Q20: Students might feel anxious because they are unsure about their career direction. Could you provide some guidance based on your own experience?

It’s important to follow market trends closely, to anticipate, to be flexible, and to some extent, to be willing to pivot to where the work is or will soon be. For example, in the US, bankruptcy is one practice area that people often mention when there’s an economic downturn, as offering a steady flow of work during difficult economic times. A practice area that could be seen as contrasting with bankruptcy is Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A), where the amount of available work can be quite volatile over time, and particularly limited during difficult economic times. When you are staffed on matters as a junior lawyer, it is important to learn as much as you can. Pay close attention to what everyone is contributing. Learn from everyone, including, of course, the senior lawyers on the team.

Q21: This year marks STL's 15th anniversary. Do you have any expectations for STL, its current students, and its alumni?

We are no longer a startup; we are an established institution with an established alumni network. Our accomplishments over the past 15 years - and importantly, I include in that set the accomplishments of our alumni - should be a key factor for recruiting, whether in the context of prospective students, new staff hires, or new additions to our faculty. When STL was established in 2008, we were unique. What is compelling, and exciting, is that we are just as unique in 2023. Our model is difficult to replicate. That was an enormous advantage in 2008, and that advantage is equally significant in 2023. What we certainly did not have in 2008 was 1,000 alumni, making significant contributions throughout China and throughout the world, with a deep, lasting commitment to the school. STL’s future is promising.

*This interview was conducted, written, and translated by Feng Chi, Li Chaoqun, Lu Qing, Sun Fanshu, and Yin Xinyi; it was proofread by Lu Qing and Sun Fanshu.